top of page

Cities for People

January 28, 2026

“City by people and for people.” (Gehl, 2010, p. 29)

After relocating to Ann Arbor and settling in for nearly a month, I finally found a quiet moment to revisit Cities for People by Jan Gehl (Island Press). I first read the book last month, and its arguments resonate with the course I am currently teaching—Design Ethnography Methods (UT 210) in Urban Technology.

I am drawn to how Gehl foregrounds the human dimension as the starting point for urban analysis. He invites us to read and walk through the city at eye level (p. 117), emphasizing that urban form should support lively, safe, sustainable, and healthy cities (p. 61). For decades, the human dimension has been overlooked in urban planning (p. 3). This critique echoes earlier challenges to modernist urbanism, most notably Jane Jacobs’s The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961), which positioned quality of living as a central urban value.

Another concept that inspires me is “life between buildings.” This idea captures the wide range of everyday activities that unfold in shared urban spaces: window shopping, commuting, walking dogs, exercising, street dancing, or simply pausing for a moment (p. 19). These ordinary yet meaningful interactions constitute the city's social fabric. Closely related is the discussion of soft edges (p. 75): when thoughtfully designed, edges function not as rigid boundaries but as exchange zones or places to linger, encouraging interaction, observation, and participation rather than mere movement. Boundaries are defined and shaped by people’s everyday lifestyles.

These ideas can link to urbanist and sociologist William H. Whyte’s notion of “100% places” in City: Rediscovering the Center (1988). He describes these as spaces where the essential qualities of good city life converge, where users’ needs merge seamlessly with attention to detail and environmental coherence (p. 177). As an open and accessible interface between people, city space becomes a critical arena for everyday life and for multigenerational purposes. The city functions as a meeting place in a social sense (p. 28), accommodating both small-scale encounters and large collective events, as well as diverse demographics and complex cultural entanglement. Ultimately, this reinforces Gehl’s core proposition: the city is by people and for people (p. 29).

“City by people and for people.” (Gehl, 2010, p. 29)

After relocating to Ann Arbor and settling in for nearly a month, I finally found a quiet moment to revisit Cities for People by Jan Gehl (Island Press). I first read the book last month, and its arguments resonate with the course I am currently teaching—Design Ethnography Methods (UT 210) in Urban Technology.

I am drawn to how Gehl foregrounds the human dimension as the starting point for urban analysis. He invites us to read and walk through the city at eye level (p. 117), emphasizing that urban form should support lively, safe, sustainable, and healthy cities (p. 61). For decades, the human dimension has been overlooked in urban planning (p. 3). This critique echoes earlier challenges to modernist urbanism, most notably Jane Jacobs’s The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961), which positioned quality of living as a central urban value.

Another concept that inspires me is “life between buildings.” This idea captures the wide range of everyday activities that unfold in shared urban spaces: window shopping, commuting, walking dogs, exercising, street dancing, or simply pausing for a moment (p. 19). These ordinary yet meaningful interactions constitute the city's social fabric. Closely related is the discussion of soft edges (p. 75): when thoughtfully designed, edges function not as rigid boundaries but as exchange zones or places to linger, encouraging interaction, observation, and participation rather than mere movement. Boundaries are defined and shaped by people’s everyday lifestyles.

These ideas can link to urbanist and sociologist William H. Whyte’s notion of “100% places” in City: Rediscovering the Center (1988). He describes these as spaces where the essential qualities of good city life converge, where users’ needs merge seamlessly with attention to detail and environmental coherence (p. 177). As an open and accessible interface between people, city space becomes a critical arena for everyday life and for multigenerational purposes. The city functions as a meeting place in a social sense (p. 28), accommodating both small-scale encounters and large collective events, as well as diverse demographics and complex cultural entanglement. Ultimately, this reinforces Gehl’s core proposition: the city is by people and for people (p. 29).

Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity

January 10, 2026

“Learning is the engine of practice, and practice is the history of learning” (Wenger, 1998, P96).

On my flight from Boston to Detroit, what should have been a routine two-hour journey stretched to eight hours due to snow. The extra time spent waiting at the airport offered a rare moment to revisit Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity by Etienne Wenger (Cambridge University Press, 1998).

Social learning theorist Wenger offers a compelling rethinking of learning as a fundamentally social phenomenon, situated within communities rather than isolated individuals. His social theory of learning consists of four interrelated components (P5): meaning (learning as experience), practice (learning as doing), community (learning as belonging), and identity (learning as becoming).

Central to this argument is the notion that learning and practice are inseparable. Learning drives practice, while practice embodies accumulated histories of learning (P87 and P96). Practice is neither static nor fixed; instead, it evolves through a dynamic interplay of continuity and discontinuity (P93). Practice is like a property of a community, characterized by mutual engagement, a joint enterprise, and a shared repertoire of resources, stories, and tools (P73).

The development of practice unfolds over time, yet what defines a Community of Practice (CoP) is not simply duration. Rather, it is the sustained quality of mutual engagement, people working together long enough to pursue a shared enterprise and generate meaningful learning. From this perspective, CoP can be understood as shared histories of learning (P86).

Because learning reshapes who we are and what we are capable of doing, it is inherently a projection of identity or status (P215). Learning should not be reduced to one-directional, classroom-based instruction. Instead, it is a form of social learning that enables designers to encounter real-world challenges, engage with communities, and empower service providers and key stakeholders. In this sense, social learning functions as contextual knowledge, challenging the assumption that knowledge is a static asset. Rather, knowledge is a sensorial, memorable, relational, and personal experience that emerges through participation. It is through this ongoing formation of identity that learning becomes a source of meaning and personal and social energy (P215).

“Learning is the engine of practice, and practice is the history of learning” (Wenger, 1998, P96).

On my flight from Boston to Detroit, what should have been a routine two-hour journey stretched to eight hours due to snow. The extra time spent waiting at the airport offered a rare moment to revisit Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity by Etienne Wenger (Cambridge University Press, 1998).

Social learning theorist Wenger offers a compelling rethinking of learning as a fundamentally social phenomenon, situated within communities rather than isolated individuals. His social theory of learning consists of four interrelated components (P5): meaning (learning as experience), practice (learning as doing), community (learning as belonging), and identity (learning as becoming).

Central to this argument is the notion that learning and practice are inseparable. Learning drives practice, while practice embodies accumulated histories of learning (P87 and P96). Practice is neither static nor fixed; instead, it evolves through a dynamic interplay of continuity and discontinuity (P93). Practice is like a property of a community, characterized by mutual engagement, a joint enterprise, and a shared repertoire of resources, stories, and tools (P73).

The development of practice unfolds over time, yet what defines a Community of Practice (CoP) is not simply duration. Rather, it is the sustained quality of mutual engagement, people working together long enough to pursue a shared enterprise and generate meaningful learning. From this perspective, CoP can be understood as shared histories of learning (P86).

Because learning reshapes who we are and what we are capable of doing, it is inherently a projection of identity or status (P215). Learning should not be reduced to one-directional, classroom-based instruction. Instead, it is a form of social learning that enables designers to encounter real-world challenges, engage with communities, and empower service providers and key stakeholders. In this sense, social learning functions as contextual knowledge, challenging the assumption that knowledge is a static asset. Rather, knowledge is a sensorial, memorable, relational, and personal experience that emerges through participation. It is through this ongoing formation of identity that learning becomes a source of meaning and personal and social energy (P215).

Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation

December 26, 2025

I’m currently preparing a book chapter on cross- and interdisciplinary learning through the lens of Communities of Practice (CoP), during the Christmas break in New York. While revisiting foundational literature, the classic Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation by Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger (Cambridge University Press) caught my attention, perhaps as a way to keep my thinking warm in the cold weather. Although it is not the most recent learning theory, I find myself drawn to the authors' careful construction of the concepts of CoP and legitimate peripheral participation (LPP).

A CoP can be understood as a group of people who share a common interest, craft, or profession and learn together through ongoing interaction and the exchange of experience (Bloch et al., 2014). We can think of a CoP as a set of relations among people, activities, and the world—relations that evolve over time and intersect with other overlapping communities of practice (P98). This framing highlights three closely intertwined dimensions: community, domain, and practice. Learning, from this perspective, is not a discrete or isolated event but something embedded in complex sociocultural contexts.

This view stands in contrast to more traditional models of learning that treat it as an individual process of knowledge acquisition with a clear beginning and end. Instead, learning is understood as an integral and inseparable part of social practice (P31). The emphasis shifts away from the individual learner and toward learning as participation in the social world, and from narrowly defined cognitive processes to a broader understanding of practice itself (P43).

LPP sits at the center of this argument. Learners inevitably participate in CoPs, and developing knowledge and skill involves gradually moving toward fuller participation in a community’s sociocultural practices (P29). LPP gains its meaning through the dynamic relationships among people, activities, ways of knowing, and the world. Learning, in this sense, can unfold over extended periods of time and resists being neatly bounded or measured.

In the era of AI, this way of thinking feels relevant. Technologies have made knowledge more accessible, lowered barriers to skill acquisition, and enabled far more flexible ways of working and living. The AI-enabled conditions invite us to rethink how learning happens over time and across contexts, exploring new approaches to continuous learning, shaping resilient design leadership, and building sociocultural infrastructures.

I’m currently preparing a book chapter on cross- and interdisciplinary learning through the lens of Communities of Practice (CoP), during the Christmas break in New York. While revisiting foundational literature, the classic Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation by Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger (Cambridge University Press) caught my attention, perhaps as a way to keep my thinking warm in the cold weather. Although it is not the most recent learning theory, I find myself drawn to the authors' careful construction of the concepts of CoP and legitimate peripheral participation (LPP).

A CoP can be understood as a group of people who share a common interest, craft, or profession and learn together through ongoing interaction and the exchange of experience (Bloch et al., 2014). We can think of a CoP as a set of relations among people, activities, and the world—relations that evolve over time and intersect with other overlapping communities of practice (P98). This framing highlights three closely intertwined dimensions: community, domain, and practice. Learning, from this perspective, is not a discrete or isolated event but something embedded in complex sociocultural contexts.

This view stands in contrast to more traditional models of learning that treat it as an individual process of knowledge acquisition with a clear beginning and end. Instead, learning is understood as an integral and inseparable part of social practice (P31). The emphasis shifts away from the individual learner and toward learning as participation in the social world, and from narrowly defined cognitive processes to a broader understanding of practice itself (P43).

LPP sits at the center of this argument. Learners inevitably participate in CoPs, and developing knowledge and skill involves gradually moving toward fuller participation in a community’s sociocultural practices (P29). LPP gains its meaning through the dynamic relationships among people, activities, ways of knowing, and the world. Learning, in this sense, can unfold over extended periods of time and resists being neatly bounded or measured.

In the era of AI, this way of thinking feels relevant. Technologies have made knowledge more accessible, lowered barriers to skill acquisition, and enabled far more flexible ways of working and living. The AI-enabled conditions invite us to rethink how learning happens over time and across contexts, exploring new approaches to continuous learning, shaping resilient design leadership, and building sociocultural infrastructures.

Uncommon Service: How to Win by Putting Customers at the Core of Your Business

December 20, 2025

Service Excellence = Design × Culture

As a designer and scholar interested in service innovation, I was intrigued when Amazon recommended Uncommon Service: How to Win by Putting Customers at the Core of Your Business by Frances Frei and Anne Morriss (Harvard Business Review Press).

One idea from the book resonated with me: Service Excellence = Design × Culture. This deceptively simple expression underscores a critical insight: service excellence is not achieved through design or culture alone, but through their interaction.

The authors argue that service excellence depends on deliberate trade-offs across four “service truths” (P6): 1. service offering: Which specific attributes of service are you competing on? 2. Funding mechanism: How is excellence paid for? 3. Employee management system: Are employees set up for success? And 4. Customer management system: How are customers managed and trained?

Design is often the visible dimension of service, such as spaces, furniture, and interfaces. Because of the tangibility, the design is relatively easy to modify. We can renovate an office, replace furniture, or update a digital interface.

Culture, by contrast, operates more quietly yet powerfully. It functions as a form of what might be called “absentee leadership”, shaping behavior without constant oversight (P8). Culture is embedded in rituals, events, performance metrics, and shared norms within offices or labs. A strong culture can sometimes compensate for weaker design, while a poorly aligned culture can undermine even the most sophisticated service innovation.

As the authors note, “Culture doesn’t just tell you what to do. It shows you how to think.” (P8). David Kelley, co-founder of IDEO, described the firm’s ethos as “enlightened trial and error”—a phrase that encapsulates IDEO’s culture of rapid prototyping, experimentation, and learning (Perry, 1995; P161).

The enduring question the book raises is not simply what service excellence looks like, but how it is sustained: how cultures of service excellence are built, shaped, and what happens inside organizations that consistently achieve this elusive goal (P163).

Service Excellence = Design × Culture

As a designer and scholar interested in service innovation, I was intrigued when Amazon recommended Uncommon Service: How to Win by Putting Customers at the Core of Your Business by Frances Frei and Anne Morriss (Harvard Business Review Press).

One idea from the book resonated with me: Service Excellence = Design × Culture. This deceptively simple expression underscores a critical insight: service excellence is not achieved through design or culture alone, but through their interaction.

The authors argue that service excellence depends on deliberate trade-offs across four “service truths” (P6): 1. service offering: Which specific attributes of service are you competing on? 2. Funding mechanism: How is excellence paid for? 3. Employee management system: Are employees set up for success? And 4. Customer management system: How are customers managed and trained?

Design is often the visible dimension of service, such as spaces, furniture, and interfaces. Because of the tangibility, the design is relatively easy to modify. We can renovate an office, replace furniture, or update a digital interface.

Culture, by contrast, operates more quietly yet powerfully. It functions as a form of what might be called “absentee leadership”, shaping behavior without constant oversight (P8). Culture is embedded in rituals, events, performance metrics, and shared norms within offices or labs. A strong culture can sometimes compensate for weaker design, while a poorly aligned culture can undermine even the most sophisticated service innovation.

As the authors note, “Culture doesn’t just tell you what to do. It shows you how to think.” (P8). David Kelley, co-founder of IDEO, described the firm’s ethos as “enlightened trial and error”—a phrase that encapsulates IDEO’s culture of rapid prototyping, experimentation, and learning (Perry, 1995; P161).

The enduring question the book raises is not simply what service excellence looks like, but how it is sustained: how cultures of service excellence are built, shaped, and what happens inside organizations that consistently achieve this elusive goal (P163).

デザインの骨格

December 16, 2025

I came across Shunji Yamanaka’s Skeletal Structure of Design (デザインの骨格) at an Eslite bookstore during a recent visit to Taipei. I am not entirely sure whether this is the exact English title, as I purchased the Chinese edition.

With training in both industrial design and electrical engineering, Yamanaka articulates a design philosophy that is both rigorous and inclusive. Prototyping plays a critical role in his practice, not merely as a means of making, but as a way of strategizing. Through prototyping, he thinks visually and, in turn, writes visually (P173).

The book is a curated collection of his blog posts from 2009 to 2010, presented in the style of design diaries. Each short essay, paired with a single photograph, reads like an independent piece of ethnographic inquiry. Together, they reinforce his central argument: that the essence of design lies in its structure—namely, its components and the ways they are configured (P243). I read Yamanaka’s use of “structure” as a metaphor for adopting a systems-oriented lens in design.

Yamanaka also reflects on his collaborations and exchanges with Japanese designers, engineers, and artists, including Naoto Fukasawa (former product designer at IDEO) (P190), Toshiyuki Inoko (founder of teamLab) (P212), Novmichi Tosa (founder of Maywa Denki) (P210), Hiroshi Ishii (Director of the MIT Media Lab’s Tangible Media Group) (P216), Taku Satoh (graphic designer) (P218), Masahiko Sato (composer) (P220), and Tokujin Yoshioka (designer) (P222).

What I appreciate most is Yamanaka’s authenticity and openness in confronting design challenges. He suggests that caring for and carefully measuring feeling, by attuning oneself to subtle sensations and intuitions, is a critical first step in the creative process (P182).

I came across Shunji Yamanaka’s Skeletal Structure of Design (デザインの骨格) at an Eslite bookstore during a recent visit to Taipei. I am not entirely sure whether this is the exact English title, as I purchased the Chinese edition.

With training in both industrial design and electrical engineering, Yamanaka articulates a design philosophy that is both rigorous and inclusive. Prototyping plays a critical role in his practice, not merely as a means of making, but as a way of strategizing. Through prototyping, he thinks visually and, in turn, writes visually (P173).

The book is a curated collection of his blog posts from 2009 to 2010, presented in the style of design diaries. Each short essay, paired with a single photograph, reads like an independent piece of ethnographic inquiry. Together, they reinforce his central argument: that the essence of design lies in its structure—namely, its components and the ways they are configured (P243). I read Yamanaka’s use of “structure” as a metaphor for adopting a systems-oriented lens in design.

Yamanaka also reflects on his collaborations and exchanges with Japanese designers, engineers, and artists, including Naoto Fukasawa (former product designer at IDEO) (P190), Toshiyuki Inoko (founder of teamLab) (P212), Novmichi Tosa (founder of Maywa Denki) (P210), Hiroshi Ishii (Director of the MIT Media Lab’s Tangible Media Group) (P216), Taku Satoh (graphic designer) (P218), Masahiko Sato (composer) (P220), and Tokujin Yoshioka (designer) (P222).

What I appreciate most is Yamanaka’s authenticity and openness in confronting design challenges. He suggests that caring for and carefully measuring feeling, by attuning oneself to subtle sensations and intuitions, is a critical first step in the creative process (P182).

Nature-Centered Design: When We Learn the Dialogue of Flowers

December 11, 2025

“A design not born of a human centre, but of a living entanglement, of a dialogue like that of flowers – a Nature-Centered Design.” (P80)

I was fortunate to review Carla Paoliello’s latest book, Nature-Centered Design: When We Learn the Dialogue of Flowers. Her work offered me a meaningful space to reflect on the emerging notion of Design for Longevity (D4L).

Nature-Centered Design is a gentle design. It invites us to design with mindfulness, to choose harmony with the planet, and to imagine a world free from pollution, extinction, slavery, inequality, and social injustice (P53). It is, at its core, a design of caring. For example, in our everyday lives, we are constantly practicing the art of accompanying, walking alongside without overshadowing, protecting without dominating, guiding without imposing (P58).

Accompanying naturally extends into relationality. Relationships, in this view, form a dynamic field of intra-, situational, ideological, and positional relationships (P32). Life is therefore not an isolated bubble, but a choreography intertwined with the environment—a “dance with the environment,” as Carla describes it (P16).

Within this framework, Carla encourages us to rethink artifacts not only at the moment of their creation but across their entire life cycle. Every object carries systems within it—revealing immaterial layers and telling stories of bodies, identities, rituals, and traces. To honestly think about an object, she writes, is to listen to the raw material and its origins, to the ways of life that touch and transform it (P67).

“A design not born of a human centre, but of a living entanglement, of a dialogue like that of flowers – a Nature-Centered Design.” (P80)

I was fortunate to review Carla Paoliello’s latest book, Nature-Centered Design: When We Learn the Dialogue of Flowers. Her work offered me a meaningful space to reflect on the emerging notion of Design for Longevity (D4L).

Nature-Centered Design is a gentle design. It invites us to design with mindfulness, to choose harmony with the planet, and to imagine a world free from pollution, extinction, slavery, inequality, and social injustice (P53). It is, at its core, a design of caring. For example, in our everyday lives, we are constantly practicing the art of accompanying, walking alongside without overshadowing, protecting without dominating, guiding without imposing (P58).

Accompanying naturally extends into relationality. Relationships, in this view, form a dynamic field of intra-, situational, ideological, and positional relationships (P32). Life is therefore not an isolated bubble, but a choreography intertwined with the environment—a “dance with the environment,” as Carla describes it (P16).

Within this framework, Carla encourages us to rethink artifacts not only at the moment of their creation but across their entire life cycle. Every object carries systems within it—revealing immaterial layers and telling stories of bodies, identities, rituals, and traces. To honestly think about an object, she writes, is to listen to the raw material and its origins, to the ways of life that touch and transform it (P67).

Section: Kris Yao Artech

December 8, 2025

I am fortunate to have had the opportunity to visit Kris Yao Artech to discuss future collaboration with the University of Michigan and the d-mix lab during my short stay in Taipei. As a long-time admirer of Kris Yao’s work, I am not only inspired by his architectural projects but also profoundly moved by his design philosophy and life. Yao’s architecture often reinterprets traditional Chinese culture through contemporary forms—whether drawing on the expressive qualities and imagery of calligraphy (P19) or embedding a sense of spirituality into spatial thinking (P16).

Yao denoted the concept of tang ao (堂奧), where two simple syllables capture the essence of architectural creation by representing both the seen and the unseen (P5). Tang refers to the visible room, hall, or space one encounters upon entering through an open door. Ao, its counterpart, signifies what cannot be directly seen but can be sensed, imagined, and mentally constructed through its relationship with tang.

Reflecting on tang ao from a service design perspective, I think about the interplay between physical and virtual touchpoints across a user journey. In many ways, tang ao mirrors systems thinking—an embedded logic that shapes experiences through architectural, psychological, and social layers.

For instance, in the design for the Taipei City Concert Hall and Library, the idea of being “amid the streets” is thoughtfully integrated into the diverse urban surroundings. The resulting environment accommodates both formal and informal cultural activities, projecting Yao’s philosophy in harmonizing public life with architectural intent (P114).

I was especially touched by Yao’s story about his advisor, Prof. Han Pao-Teh (漢寶德). His work on the Han Pao-Teh Memorial Museum in Tainan beautifully honors Prof. Han’s profound contributions to architectural and design education and Taiwanese society. The concept of a “cube within a cube” conveys the multiplicity of Han’s intellectual legacy: the cube’s many faces symbolize his diverse expertise, while the cube’s strength and materiality pay tribute to his resilient spirit (P332).

I am fortunate to have had the opportunity to visit Kris Yao Artech to discuss future collaboration with the University of Michigan and the d-mix lab during my short stay in Taipei. As a long-time admirer of Kris Yao’s work, I am not only inspired by his architectural projects but also profoundly moved by his design philosophy and life. Yao’s architecture often reinterprets traditional Chinese culture through contemporary forms—whether drawing on the expressive qualities and imagery of calligraphy (P19) or embedding a sense of spirituality into spatial thinking (P16).

Yao denoted the concept of tang ao (堂奧), where two simple syllables capture the essence of architectural creation by representing both the seen and the unseen (P5). Tang refers to the visible room, hall, or space one encounters upon entering through an open door. Ao, its counterpart, signifies what cannot be directly seen but can be sensed, imagined, and mentally constructed through its relationship with tang.

Reflecting on tang ao from a service design perspective, I think about the interplay between physical and virtual touchpoints across a user journey. In many ways, tang ao mirrors systems thinking—an embedded logic that shapes experiences through architectural, psychological, and social layers.

For instance, in the design for the Taipei City Concert Hall and Library, the idea of being “amid the streets” is thoughtfully integrated into the diverse urban surroundings. The resulting environment accommodates both formal and informal cultural activities, projecting Yao’s philosophy in harmonizing public life with architectural intent (P114).

I was especially touched by Yao’s story about his advisor, Prof. Han Pao-Teh (漢寶德). His work on the Han Pao-Teh Memorial Museum in Tainan beautifully honors Prof. Han’s profound contributions to architectural and design education and Taiwanese society. The concept of a “cube within a cube” conveys the multiplicity of Han’s intellectual legacy: the cube’s many faces symbolize his diverse expertise, while the cube’s strength and materiality pay tribute to his resilient spirit (P332).

Slow Looking: The Art and Practice of Learning Through Observation

November 27, 2025

During the Thanksgiving break, while preparing my HCII paper and my UT210 Design Ethnography Methods course at UMich, I found Shari Tishman’s Slow Looking: The Art and Practice of Learning Through Observation (Routledge). Slow looking is a mode of learning grounded in prolonged, attentive observation (P2). Consider the patience of a wildlife photographer waiting to capture a sequence of revealing behaviors in nature (P19), or the quiet immersion of birdwatching in one’s backyard (P8). Such practices take time; they require lingering, attuning, and reflecting because the goal is to perceive subtle movements and implicit patterns in the environment. Slow looking thus serves as an important counterbalance to our natural human tendency toward fast, surface-level perception (P5).

“Looking closely” is a shared human value (P7). Many of us have experienced moments when we looked at something but did not truly see it (P40). The novelist Marcel Proust captured this spirit of perceptual renewal when he wrote, “The real act of discovery consists not in finding new lands, but in seeing with new eyes” (P36). Slow looking invites this deeper form of awareness, an orientation in which we look not only with our eyes, but with attention, emotion, and empathy. Importantly, slow looking is not limited to the visual; it can also involve touch, smell, and even taste (P18), broadening the sensory modes through which we come to understand the world around us.

Description functions as the engine of slow looking (P49). It is the process of representing how something appears in order to capture or convey a vivid sense of its qualities (P48). This invites a generative question: What makes a description a description? (P50). Scholar Werner Wolf (2007) describes description as a “cognitive frame,” a structure that shapes how we perceive and construct meaning. Through this frame, slow looking becomes not just observational but also reflective and interpretive.

Ultimately, slow looking is a form of active thinking. Tishman notes that it plays a valuable role in both critical thinking and creative problem-solving (P149). I am especially drawn to her diagram of the continuum of thinking-centered learning outcomes (P148), which differentiates between processes of discerning (e.g., describing, depicting) and processes of deciding (e.g., resolving, taking action). Within this continuum, slow looking enhances learning by revealing the complexity of parts and interactions, perspectives, and engagement. It encourages learners, educators, and designers to think and act with care, cultivating a richer, more mindful relationship with the world.

During the Thanksgiving break, while preparing my HCII paper and my UT210 Design Ethnography Methods course at UMich, I found Shari Tishman’s Slow Looking: The Art and Practice of Learning Through Observation (Routledge). Slow looking is a mode of learning grounded in prolonged, attentive observation (P2). Consider the patience of a wildlife photographer waiting to capture a sequence of revealing behaviors in nature (P19), or the quiet immersion of birdwatching in one’s backyard (P8). Such practices take time; they require lingering, attuning, and reflecting because the goal is to perceive subtle movements and implicit patterns in the environment. Slow looking thus serves as an important counterbalance to our natural human tendency toward fast, surface-level perception (P5).

“Looking closely” is a shared human value (P7). Many of us have experienced moments when we looked at something but did not truly see it (P40). The novelist Marcel Proust captured this spirit of perceptual renewal when he wrote, “The real act of discovery consists not in finding new lands, but in seeing with new eyes” (P36). Slow looking invites this deeper form of awareness, an orientation in which we look not only with our eyes, but with attention, emotion, and empathy. Importantly, slow looking is not limited to the visual; it can also involve touch, smell, and even taste (P18), broadening the sensory modes through which we come to understand the world around us.

Description functions as the engine of slow looking (P49). It is the process of representing how something appears in order to capture or convey a vivid sense of its qualities (P48). This invites a generative question: What makes a description a description? (P50). Scholar Werner Wolf (2007) describes description as a “cognitive frame,” a structure that shapes how we perceive and construct meaning. Through this frame, slow looking becomes not just observational but also reflective and interpretive.

Ultimately, slow looking is a form of active thinking. Tishman notes that it plays a valuable role in both critical thinking and creative problem-solving (P149). I am especially drawn to her diagram of the continuum of thinking-centered learning outcomes (P148), which differentiates between processes of discerning (e.g., describing, depicting) and processes of deciding (e.g., resolving, taking action). Within this continuum, slow looking enhances learning by revealing the complexity of parts and interactions, perspectives, and engagement. It encourages learners, educators, and designers to think and act with care, cultivating a richer, more mindful relationship with the world.

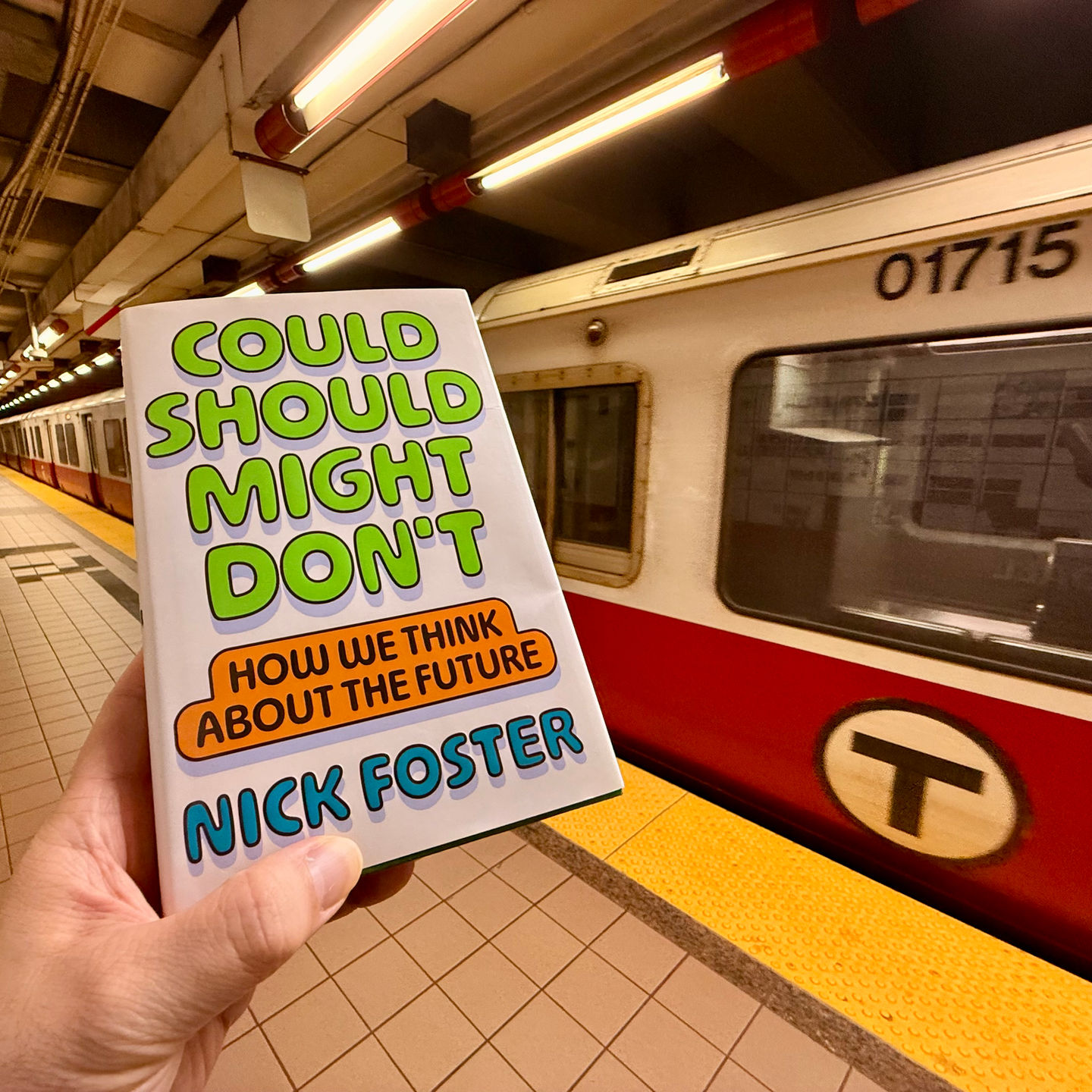

Could Should Might Don't: How We Think About the Future

November 22, 2025

Nick Foster’s latest book, Could Should Might Don’t: How We Think About the Future, accompanied me on my Red Line commutes during my final winter on the MIT campus. Foster and I served together on the jury for the International Design Excellence Awards (IDEA) in 2017–18.

The book offers a rich constellation of classic theories, such as Voros’s (2000) Futures Cone outlining the probable, plausible, and possible (P183), and Jay Wright Forrester’s system dynamics (P244), alongside vivid examples including the Museum of the Future in Dubai and its immersive public futures experiences (P75), Walt Disney’s Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow (EPCOT), which sought to transform the narrative ambition of science fiction into an actual city of the future (P69), and Danny Hillis and Stewart Brand’s Long Now Foundation, established to promote “long-term thinking” (P200). Together, these theories and cases enable Foster to develop his notion of a “collective future” (P77).

I was particularly struck by his discussion of the “Future Mundane” (P322). Foster writes that “the future is a place where we can let our imaginations gambol freely, a place where we can dream about other ways of being or push ourselves to imagine ambitious change” (P320). Yet he also reminds us that “the mundane is ordinary, everyday, boring, humdrum, middling, and basic” (P307). Taken together, these ideas suggest that the future can be understood as an ordinary place, not defined by prediction or spectacle, but by attentive and imaginative engagement with everyday life. There are no diagrams, frameworks, or magical techniques that make someone better at “doing the future”; nor are there forecasts or projections in his book (P39). Instead, we can approach the future through grounded, critical, and imaginative inquiry.

This notion of the Future Mundane immediately resonated with Sarah Pink et al.’s (2017) concept of “mundane data” as an analytical counterpoint to big data. Whereas big data is frequently framed as novel, spectacular, disruptive, or revolutionary, mundane data is quiet, relational, open, and often “leaky”—a generative space where routines, improvisations, and everyday accomplishments unfold and remain perpetually unfinished. The mundane has long held a central place in the social sciences and humanities, often associated with “rendering the invisible visible and exposing the mundane” (Galloway, 2004, p. 385).

Reading Foster while recalling Pink’s work felt like being in dialogue with both—moving fluidly between books, concepts, and future imaginings (P197).

Nick Foster’s latest book, Could Should Might Don’t: How We Think About the Future, accompanied me on my Red Line commutes during my final winter on the MIT campus. Foster and I served together on the jury for the International Design Excellence Awards (IDEA) in 2017–18.

The book offers a rich constellation of classic theories, such as Voros’s (2000) Futures Cone outlining the probable, plausible, and possible (P183), and Jay Wright Forrester’s system dynamics (P244), alongside vivid examples including the Museum of the Future in Dubai and its immersive public futures experiences (P75), Walt Disney’s Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow (EPCOT), which sought to transform the narrative ambition of science fiction into an actual city of the future (P69), and Danny Hillis and Stewart Brand’s Long Now Foundation, established to promote “long-term thinking” (P200). Together, these theories and cases enable Foster to develop his notion of a “collective future” (P77).

I was particularly struck by his discussion of the “Future Mundane” (P322). Foster writes that “the future is a place where we can let our imaginations gambol freely, a place where we can dream about other ways of being or push ourselves to imagine ambitious change” (P320). Yet he also reminds us that “the mundane is ordinary, everyday, boring, humdrum, middling, and basic” (P307). Taken together, these ideas suggest that the future can be understood as an ordinary place, not defined by prediction or spectacle, but by attentive and imaginative engagement with everyday life. There are no diagrams, frameworks, or magical techniques that make someone better at “doing the future”; nor are there forecasts or projections in his book (P39). Instead, we can approach the future through grounded, critical, and imaginative inquiry.

This notion of the Future Mundane immediately resonated with Sarah Pink et al.’s (2017) concept of “mundane data” as an analytical counterpoint to big data. Whereas big data is frequently framed as novel, spectacular, disruptive, or revolutionary, mundane data is quiet, relational, open, and often “leaky”—a generative space where routines, improvisations, and everyday accomplishments unfold and remain perpetually unfinished. The mundane has long held a central place in the social sciences and humanities, often associated with “rendering the invisible visible and exposing the mundane” (Galloway, 2004, p. 385).

Reading Foster while recalling Pink’s work felt like being in dialogue with both—moving fluidly between books, concepts, and future imaginings (P197).

Ethonography for Designers

November 15, 2025

As I prepare for my upcoming course, UT210 Design Ethnography Methods at the University of Michigan, I revisited a valuable resource for the class: Ethnography for Designers by Galen Cranz (Routledge). Chapter 2, “The Ethnographic Design Project” (P16), is especially useful. It outlines a guided process that includes developing a research proposal, identifying cultural informants, creating taxonomies, conducting a literature review, exploring redesign opportunities, sharing results, and composing the final report.

Ethnography is one way to translate understanding of people into the design of places (P42). Its primary objective is to describe a culture—literally, describing (graphing) people (ethno) (P14). In an ethnographic design project, the designer’s task is not to study people, but to learn from them (P42) while navigating among personal perspectives and both etic (outsider, e.g., literature review) and emic (insider, e.g., field observation) viewpoints (P93).

The book builds on the notion of semantic ethnography (P30), a “process of discovering and describing a culture” through informant interviews that reveal explicit cultural knowledge (McCurdy et al., 2005, p. 9). I also appreciate Cranz’s emphasis on sited micro-cultures—focused, small-scale cultural contexts (P43) that help designers better interpret the broader cultural landscape. These sited micro-cultures enable more precise definitions, richer descriptions, and more grounded design responses for specific groups (P19).

Cranz offers a memorable metaphor: “Children often act like ethnographers—they ask questions to discover what other people believe, what they mean by the words they use, and which forms of behavior are appropriate. And they are able to report their findings to their friends.” (P19). I believe this childlike curiosity—humble, hungry, and deeply human—is essential for sharpening our ethnographic sensibilities and developing design practices that contribute to positive social impact.

As I prepare for my upcoming course, UT210 Design Ethnography Methods at the University of Michigan, I revisited a valuable resource for the class: Ethnography for Designers by Galen Cranz (Routledge). Chapter 2, “The Ethnographic Design Project” (P16), is especially useful. It outlines a guided process that includes developing a research proposal, identifying cultural informants, creating taxonomies, conducting a literature review, exploring redesign opportunities, sharing results, and composing the final report.

Ethnography is one way to translate understanding of people into the design of places (P42). Its primary objective is to describe a culture—literally, describing (graphing) people (ethno) (P14). In an ethnographic design project, the designer’s task is not to study people, but to learn from them (P42) while navigating among personal perspectives and both etic (outsider, e.g., literature review) and emic (insider, e.g., field observation) viewpoints (P93).

The book builds on the notion of semantic ethnography (P30), a “process of discovering and describing a culture” through informant interviews that reveal explicit cultural knowledge (McCurdy et al., 2005, p. 9). I also appreciate Cranz’s emphasis on sited micro-cultures—focused, small-scale cultural contexts (P43) that help designers better interpret the broader cultural landscape. These sited micro-cultures enable more precise definitions, richer descriptions, and more grounded design responses for specific groups (P19).

Cranz offers a memorable metaphor: “Children often act like ethnographers—they ask questions to discover what other people believe, what they mean by the words they use, and which forms of behavior are appropriate. And they are able to report their findings to their friends.” (P19). I believe this childlike curiosity—humble, hungry, and deeply human—is essential for sharpening our ethnographic sensibilities and developing design practices that contribute to positive social impact.

Design Empathy and Contextual Awareness

A 13-hour direct flight from Boston to Dubai Design Week calls for good reading material. Fortunately, I brought Wayne Li’s latest book, Design Empathy and Contextual Awareness (Laurence King Publishing).

Design empathy can be perceived as encompassing multiple layers of understanding. As the saying goes, “You don’t really know a person until you’ve walked a mile in their shoes” (P142). The psychologists Daniel Goleman and Paul Ekman have defined three different types of empathy: cognitive empathy, emotional empathy, and compassionate concern (P84).

Cognitive empathy is the ability to understand another’s perspective—often described as perspective-taking. Emotional empathy is the ability to share or resonate with another person’s emotional state. Compassionate concern is the overlap of the two, prompting action in support of others’ well-being. Design thinking builds upon this foundation: cultivating empathy for users, iterating through prototypes, and envisioning future possibilities through storytelling (P115).

I also appreciate the book’s practical tools, particularly the Empathy Map (P126) and the Powers of 10. The Empathy Map, structured as a 2×2 matrix, helps distinguish explicit behaviors (what individuals say and do) from implicit dimensions (what they think and feel), revealing tensions and unspoken needs. By shifting perspective across scales, Powers of 10 (P172) provides a powerful way to embed systems thinking in design—reminding us that every challenge exists within a larger system, and every detail influences the whole.

One insight that stood out from Li’s conversation with David Kelley is that while design tools and processes continue to evolve, the values that guide design remain foundational (P119). Great designers are shaped not just by the methods they employ, but by the values they hold. These values emerge from our frames of reference—the ways our frames of mind and frames of meaning intersect (P32).

Empathy, in this view, is not merely a technique; it is a core catalyst for cultivating and sustaining meaningful values in design.

Design empathy can be perceived as encompassing multiple layers of understanding. As the saying goes, “You don’t really know a person until you’ve walked a mile in their shoes” (P142). The psychologists Daniel Goleman and Paul Ekman have defined three different types of empathy: cognitive empathy, emotional empathy, and compassionate concern (P84).

Cognitive empathy is the ability to understand another’s perspective—often described as perspective-taking. Emotional empathy is the ability to share or resonate with another person’s emotional state. Compassionate concern is the overlap of the two, prompting action in support of others’ well-being. Design thinking builds upon this foundation: cultivating empathy for users, iterating through prototypes, and envisioning future possibilities through storytelling (P115).

I also appreciate the book’s practical tools, particularly the Empathy Map (P126) and the Powers of 10. The Empathy Map, structured as a 2×2 matrix, helps distinguish explicit behaviors (what individuals say and do) from implicit dimensions (what they think and feel), revealing tensions and unspoken needs. By shifting perspective across scales, Powers of 10 (P172) provides a powerful way to embed systems thinking in design—reminding us that every challenge exists within a larger system, and every detail influences the whole.

One insight that stood out from Li’s conversation with David Kelley is that while design tools and processes continue to evolve, the values that guide design remain foundational (P119). Great designers are shaped not just by the methods they employ, but by the values they hold. These values emerge from our frames of reference—the ways our frames of mind and frames of meaning intersect (P32).

Empathy, in this view, is not merely a technique; it is a core catalyst for cultivating and sustaining meaningful values in design.

Design Ethnography Research, Responsibilities, and Futures

October 31, 2025

I am preparing for my upcoming course, UT 210 Listening: Design Ethnography Methods, with great excitement, and have been exploring reference and inspirational readings. One that particularly resonated with me is Design Ethnography: Research, Responsibilities, and Futures by Sarah Pink, Vaike Fors, Debora Lanzeni, Melisa Duque, Shanti Sumartojo, and Yolande Strengers (Routledge).

I appreciate Professor Pink’s framing of design ethnography as a “blended practice” (Pink, 2021; Pink et al., 2017). As designer-researchers, we are invited to embed ourselves—to blend in, immerse, and integrate within real-world contexts—to reveal implicit observations and subtle interactions that shape people's lived experiences.

In my design and research projects, I frequently employ user journey maps and service blueprints (Shostack, 1984) to visualize critical touchpoints and potential interactions. I was especially inspired by the authors’ concept of the “routine map,” which reframes everyday travel not as a linear journey from A to B, but as a constellation of overlapping routines—grocery shopping, social visits, community activities, errands, and other daily tasks. These maps contextualize mobility within the fabric of daily life (P167).

Design ethnography does not have to result in a conventional design outcome. Rather than focusing solely on products or services, it invites us to see design as an interventional and process-driven practice—one that unfolds toward uncertain and emergent futures (P3). In this sense, a design ethnographic workshop may become less about reaching a predefined solution and more about creating the conditions for new alignments, relationships, and insights to emerge organically over time (P175). It reminds us that the value often lies in what evolves through continuous participation, dialogue, and discovery, rather than what is simply delivered at the end.

Engagement in design ethnography can be considered as a spectrum or hierarchy (Strengers et al., 2019), varying in intensity and participant involvement across decision-making and public processes (P180). Understanding such engagement involves identifying levels (spatial or temporal), types of encounters (private, public, or semi-public), and methods of documentation (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods) that, together, reveal the stories and data shaping human and non-human experiences.

Everyday designing can itself be seen as an intervention for ongoing transformation (P105)—a continuous, reflexive practice that allows ethnography to evolve alongside the very worlds it seeks to understand and redesign.

I am preparing for my upcoming course, UT 210 Listening: Design Ethnography Methods, with great excitement, and have been exploring reference and inspirational readings. One that particularly resonated with me is Design Ethnography: Research, Responsibilities, and Futures by Sarah Pink, Vaike Fors, Debora Lanzeni, Melisa Duque, Shanti Sumartojo, and Yolande Strengers (Routledge).

I appreciate Professor Pink’s framing of design ethnography as a “blended practice” (Pink, 2021; Pink et al., 2017). As designer-researchers, we are invited to embed ourselves—to blend in, immerse, and integrate within real-world contexts—to reveal implicit observations and subtle interactions that shape people's lived experiences.

In my design and research projects, I frequently employ user journey maps and service blueprints (Shostack, 1984) to visualize critical touchpoints and potential interactions. I was especially inspired by the authors’ concept of the “routine map,” which reframes everyday travel not as a linear journey from A to B, but as a constellation of overlapping routines—grocery shopping, social visits, community activities, errands, and other daily tasks. These maps contextualize mobility within the fabric of daily life (P167).

Design ethnography does not have to result in a conventional design outcome. Rather than focusing solely on products or services, it invites us to see design as an interventional and process-driven practice—one that unfolds toward uncertain and emergent futures (P3). In this sense, a design ethnographic workshop may become less about reaching a predefined solution and more about creating the conditions for new alignments, relationships, and insights to emerge organically over time (P175). It reminds us that the value often lies in what evolves through continuous participation, dialogue, and discovery, rather than what is simply delivered at the end.

Engagement in design ethnography can be considered as a spectrum or hierarchy (Strengers et al., 2019), varying in intensity and participant involvement across decision-making and public processes (P180). Understanding such engagement involves identifying levels (spatial or temporal), types of encounters (private, public, or semi-public), and methods of documentation (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods) that, together, reveal the stories and data shaping human and non-human experiences.

Everyday designing can itself be seen as an intervention for ongoing transformation (P105)—a continuous, reflexive practice that allows ethnography to evolve alongside the very worlds it seeks to understand and redesign.

Navigating Urban Exposome Futures

October 24, 2025

As a designer and design scholar, one of the most rewarding moments is engaging in conversations with people who share a similar vision and mission—and exchanging their doctoral work. I was fortunate to have a virtual coffee with Dr. Tabea Simone Sonnenschein and to read her recent book Navigating Urban Exposome Futures (Utrecht University).

The exposome refers to the totality of environmental exposures an individual experiences from conception to death and how these exposures influence health and well-being (Wild, 2005). The human exposome encompasses “the totality of exposure we face through our lives and includes the food we ingest, the air we breathe, the objects we touch, the psychological stress we face, and the activities in which we engage” that shape our health (Miller, 2014).

Sonnenschein’s research makes a valuable contribution by experimenting with agent based modeling (ABM) to explore, measure, and map the notion of the urban exposome. She emphasizes that accessible and reliable scenario-based ABMs can only be achieved through interdisciplinary collaboration and the collective development of an open-science toolbox (P13).

I am particularly inspired to extend this discussion by examining how the exposome concept evolves across scales—from the human exposome to the urban exposome and, ultimately, to the service exposome—and how these perspectives intersect with the Design for Longevity (D4L) Unclock Framework. Cities, in particular, bear immense responsibility and have the potential to address intertwined environmental, health, and social challenges, serving as dynamic hubs of population, mobility, economic activity, and resource use (P6).

As Sonnenschein insightfully notes, urban models will always remain incomplete. Many dimensions of urban life, such as the subjective experience of the city, cannot be fully captured through parameters or data. Cities are more than systems; they are living places imbued with memories, cultural meaning, and identity (P290).

Urban exposome is like an invisible fingerprint that shapes our daily lives.

As a designer and design scholar, one of the most rewarding moments is engaging in conversations with people who share a similar vision and mission—and exchanging their doctoral work. I was fortunate to have a virtual coffee with Dr. Tabea Simone Sonnenschein and to read her recent book Navigating Urban Exposome Futures (Utrecht University).

The exposome refers to the totality of environmental exposures an individual experiences from conception to death and how these exposures influence health and well-being (Wild, 2005). The human exposome encompasses “the totality of exposure we face through our lives and includes the food we ingest, the air we breathe, the objects we touch, the psychological stress we face, and the activities in which we engage” that shape our health (Miller, 2014).

Sonnenschein’s research makes a valuable contribution by experimenting with agent based modeling (ABM) to explore, measure, and map the notion of the urban exposome. She emphasizes that accessible and reliable scenario-based ABMs can only be achieved through interdisciplinary collaboration and the collective development of an open-science toolbox (P13).

I am particularly inspired to extend this discussion by examining how the exposome concept evolves across scales—from the human exposome to the urban exposome and, ultimately, to the service exposome—and how these perspectives intersect with the Design for Longevity (D4L) Unclock Framework. Cities, in particular, bear immense responsibility and have the potential to address intertwined environmental, health, and social challenges, serving as dynamic hubs of population, mobility, economic activity, and resource use (P6).

As Sonnenschein insightfully notes, urban models will always remain incomplete. Many dimensions of urban life, such as the subjective experience of the city, cannot be fully captured through parameters or data. Cities are more than systems; they are living places imbued with memories, cultural meaning, and identity (P290).

Urban exposome is like an invisible fingerprint that shapes our daily lives.

Planning for Greying Cities: Age-Friendly City Planning and Design Research and Practice

October 18, 2025

Enjoy and seize the final moments of warmth before winter descends on MIT campus, while I’m immersed in building my d-mix lab at the University of Michigan (https://d-mixlab.tcaup.umich.edu/). Recently, I found Planning for Greying Cities: Age-Friendly City Planning and Design Research and Practice (Routledge) by Prof. Tzu-Yuan Stessa Chao to be a deeply inspiring and intellectually grounding resource. It has shaped my thinking around the concept of the LongevityTech City and the future direction of my research.

I was particularly drawn to the notion of “balanced development” (P77), especially in the context of multi-generational environments and workforces. Chao’s call to transform greying cities into silver cities, through a shift from urban planning to urban governance. She advocates for a proactive, win-win approach that integrates both place-making and people-making (P165). Looking ahead, the idea that “old can be so new and grey can turn into silver” captures the transformative power of reframing, executing, and adapting (P171).

A space, as Molotch (1993) and Su et al. (2016) remind us, is not a neutral container but rather “an interlinkage of geographic form, built environment, symbolic meanings, and routines of life.” Within the age-friendly city (AFC) context, Chao identifies four spatial scales, including community/street, city, regional/rural, and national, each aligned with specific planning instruments (P34). This multiscalar framework offers a constructive lens for understanding the complex, systemic challenges that span disciplines and domains.

As noted in the United Nations’ International Guidelines on Urban and Territorial Planning (2015), urban planning today needs to extend beyond a technical exercise to become an integrative and participatory process that reconciles competing interests and aligns them toward a shared vision for the future (P171). While integration and co-creation are essential elements of this process-driven approach, Chao reminds us of an even deeper truth: “Knowledge without care or love would be dangerous, and urban life we create without love is meaningless” (P172).

Enjoy and seize the final moments of warmth before winter descends on MIT campus, while I’m immersed in building my d-mix lab at the University of Michigan (https://d-mixlab.tcaup.umich.edu/). Recently, I found Planning for Greying Cities: Age-Friendly City Planning and Design Research and Practice (Routledge) by Prof. Tzu-Yuan Stessa Chao to be a deeply inspiring and intellectually grounding resource. It has shaped my thinking around the concept of the LongevityTech City and the future direction of my research.

I was particularly drawn to the notion of “balanced development” (P77), especially in the context of multi-generational environments and workforces. Chao’s call to transform greying cities into silver cities, through a shift from urban planning to urban governance. She advocates for a proactive, win-win approach that integrates both place-making and people-making (P165). Looking ahead, the idea that “old can be so new and grey can turn into silver” captures the transformative power of reframing, executing, and adapting (P171).

A space, as Molotch (1993) and Su et al. (2016) remind us, is not a neutral container but rather “an interlinkage of geographic form, built environment, symbolic meanings, and routines of life.” Within the age-friendly city (AFC) context, Chao identifies four spatial scales, including community/street, city, regional/rural, and national, each aligned with specific planning instruments (P34). This multiscalar framework offers a constructive lens for understanding the complex, systemic challenges that span disciplines and domains.

As noted in the United Nations’ International Guidelines on Urban and Territorial Planning (2015), urban planning today needs to extend beyond a technical exercise to become an integrative and participatory process that reconciles competing interests and aligns them toward a shared vision for the future (P171). While integration and co-creation are essential elements of this process-driven approach, Chao reminds us of an even deeper truth: “Knowledge without care or love would be dangerous, and urban life we create without love is meaningless” (P172).

What It Means to Be a Designer Today: Reflections, Questions, and Ideas from AIGA’s Eye on Design

October 4, 2025

Three weeks ago, I came across What It Means to Be a Designer Today: Reflections, Questions, and Ideas from AIGA’s Eye on Design (Princeton Architectural Press) at the MIT Press Bookstore. The title immediately caught my attention, as I’ve been seeking inspiration beyond the lab, especially amid the growing intensity of my current in-person controlled experiment study.

One chapter that particularly resonated with me was Meg Miller’s “On Visual Sustainability with Benedetta Crippa” (P215). Crippa introduces the term "visual sustainability" to illustrate how graphic design can embody sustainability not only through its message or materiality, but also through its very form (P218). As she insightfully notes, “When we shift the narrative from ‘not designing’ to ‘designing within boundaries,’ we are empowered rather than suppressed” (P218).

Elizabeth Goodspeed offers another powerful reflection: “There isn’t anything new. Everything is remix” (P214). This idea underscores the importance of structural change (P220) and reminds us that meaningful, transformative design requires deliberate intention (P222) as well as considering design and design challenges as part of social infrastructure.

These perspectives led me to reflect on a question: What is the true value of design? Ric Grefé, former Executive Director of AIGA, offers a compelling response, suggesting that designers, and design itself, can be positioned as strategic thinkers and vital tools higher along the value chain within organizational structures. In doing so, they become capable of shaping concepts, strategies, and multidisciplinary collaborations that profoundly influence stakeholders and culture (P193).

I’m grateful to editors Liz Stinson and Jarrett Fuller for curating and organizing this thoughtful volume for a wide audience. As an industrial designer and electrical engineer by training, I found the book both relevant and grounding—much like my black Peu Camper, essential companions in my daily life.

Three weeks ago, I came across What It Means to Be a Designer Today: Reflections, Questions, and Ideas from AIGA’s Eye on Design (Princeton Architectural Press) at the MIT Press Bookstore. The title immediately caught my attention, as I’ve been seeking inspiration beyond the lab, especially amid the growing intensity of my current in-person controlled experiment study.

One chapter that particularly resonated with me was Meg Miller’s “On Visual Sustainability with Benedetta Crippa” (P215). Crippa introduces the term "visual sustainability" to illustrate how graphic design can embody sustainability not only through its message or materiality, but also through its very form (P218). As she insightfully notes, “When we shift the narrative from ‘not designing’ to ‘designing within boundaries,’ we are empowered rather than suppressed” (P218).

Elizabeth Goodspeed offers another powerful reflection: “There isn’t anything new. Everything is remix” (P214). This idea underscores the importance of structural change (P220) and reminds us that meaningful, transformative design requires deliberate intention (P222) as well as considering design and design challenges as part of social infrastructure.

These perspectives led me to reflect on a question: What is the true value of design? Ric Grefé, former Executive Director of AIGA, offers a compelling response, suggesting that designers, and design itself, can be positioned as strategic thinkers and vital tools higher along the value chain within organizational structures. In doing so, they become capable of shaping concepts, strategies, and multidisciplinary collaborations that profoundly influence stakeholders and culture (P193).

I’m grateful to editors Liz Stinson and Jarrett Fuller for curating and organizing this thoughtful volume for a wide audience. As an industrial designer and electrical engineer by training, I found the book both relevant and grounding—much like my black Peu Camper, essential companions in my daily life.

Design, Empathy, Interpretation: Toward Interpretive Design Research

September 24, 2025

On my way to IDC in Detroit last week, I was reading Design, Empathy, Interpretation: Toward Interpretive Design Research by Ilpo Koskinen (MIT Press). Koskinen shares a vivid story of empathic design, a research programme at Aalto University in Helsinki, Finland, which has developed an interpretive approach to design over the past two decades. The narrative is rich in contextual information and reflective moments, providing me with deeper insights into the evolution of design studies.

What struck me was the discussion about viewing users and stakeholders as sources of authority, with designers acting as interpreters (P130). Rather than treating people as subjects of instrumental value (P53), designers are called to engage with them as human beings. Codesign, for instance, redistributes authority away from the designer, enabling a more equitable and transparent process in which the designer facilitates change rather than devising solutions (P63).

Still, designers bear the responsibility of envisioning and creating. Their instruments are products, graphics, interactive devices, spaces, and systems—not just descriptions or explanations (Buchanan, 2001; P102). Human beings act on meanings (P1). The meaning of design can emerge from how we define our built environment and describe homes (P46).

These reflections push me to think more critically about timeless design, sustainable solutions, and design for longevity. As Koskinen suggests, open-ended designs should remain flexible, capable of evolving and adapting over the course of decades (P47). This resonates with my own interest in shaping design education and practice to endure, serving people and society over time.

On my way to IDC in Detroit last week, I was reading Design, Empathy, Interpretation: Toward Interpretive Design Research by Ilpo Koskinen (MIT Press). Koskinen shares a vivid story of empathic design, a research programme at Aalto University in Helsinki, Finland, which has developed an interpretive approach to design over the past two decades. The narrative is rich in contextual information and reflective moments, providing me with deeper insights into the evolution of design studies.

What struck me was the discussion about viewing users and stakeholders as sources of authority, with designers acting as interpreters (P130). Rather than treating people as subjects of instrumental value (P53), designers are called to engage with them as human beings. Codesign, for instance, redistributes authority away from the designer, enabling a more equitable and transparent process in which the designer facilitates change rather than devising solutions (P63).

Still, designers bear the responsibility of envisioning and creating. Their instruments are products, graphics, interactive devices, spaces, and systems—not just descriptions or explanations (Buchanan, 2001; P102). Human beings act on meanings (P1). The meaning of design can emerge from how we define our built environment and describe homes (P46).

These reflections push me to think more critically about timeless design, sustainable solutions, and design for longevity. As Koskinen suggests, open-ended designs should remain flexible, capable of evolving and adapting over the course of decades (P47). This resonates with my own interest in shaping design education and practice to endure, serving people and society over time.

Live Longer with AI: How artificial intelligence is helping us extend our healthspan and live better too

September 17, 2025

The fall semester has just begun, and students are once again filling the college towns of Boston and Cambridge. As I prepare to teach my Interaction Design course at Northeastern University, I am exploring the intersection of the urban exposome and the emerging concept of the LongevityTech City. In this process, I came across an insightful resource: Live Longer with AI: How Artificial Intelligence Is Helping Us Extend Our Healthspan and Live Better Too by Tina Woods (Packt).

The exposome refers to the totality of environmental exposures we experience across our lifetimes, from diet, lifestyle, and social influences on the body’s biological responses (P176). It encompasses both external factors, such as chemicals, air, water, food, and internal physiological reactions, including inflammation, stress, and infections (P193). Building on this, the urban exposome employs a spatiotemporal lens to monitor quantitative and qualitative indicators across both external and internal urban domains, thereby shaping population health and quality of life (Andrianou & Makris, 2018).

I am especially intrigued by Woods’s discussion of “life” data. Genetic, biological, behavioral, environmental, and even financial data remain underutilized (P9). Yet AI and multimodal learning present opportunities to harness this “life” data to predict disease risks, support healthier lifestyles, and reframe perceptions—from “aging as a burden” to “longevity as an opportunity” (P448).

What resonates most in Woods’s book is her reminder that AI is only a tool. The true breakthrough lies in the unprecedented cross- and transdisciplinary collaborations among scientists, businesses, and civic organizations that drive this field forward: “This is the power of the people behind the technology” (P558).

The fall semester has just begun, and students are once again filling the college towns of Boston and Cambridge. As I prepare to teach my Interaction Design course at Northeastern University, I am exploring the intersection of the urban exposome and the emerging concept of the LongevityTech City. In this process, I came across an insightful resource: Live Longer with AI: How Artificial Intelligence Is Helping Us Extend Our Healthspan and Live Better Too by Tina Woods (Packt).

The exposome refers to the totality of environmental exposures we experience across our lifetimes, from diet, lifestyle, and social influences on the body’s biological responses (P176). It encompasses both external factors, such as chemicals, air, water, food, and internal physiological reactions, including inflammation, stress, and infections (P193). Building on this, the urban exposome employs a spatiotemporal lens to monitor quantitative and qualitative indicators across both external and internal urban domains, thereby shaping population health and quality of life (Andrianou & Makris, 2018).

I am especially intrigued by Woods’s discussion of “life” data. Genetic, biological, behavioral, environmental, and even financial data remain underutilized (P9). Yet AI and multimodal learning present opportunities to harness this “life” data to predict disease risks, support healthier lifestyles, and reframe perceptions—from “aging as a burden” to “longevity as an opportunity” (P448).

What resonates most in Woods’s book is her reminder that AI is only a tool. The true breakthrough lies in the unprecedented cross- and transdisciplinary collaborations among scientists, businesses, and civic organizations that drive this field forward: “This is the power of the people behind the technology” (P558).

Modes of Criticism 4: Radical Pedagogy

September 6, 2025

Last Friday, after a long day of uninspiring meetings, I ducked into the MIT Press bookstore in search of some intellectual nourishment to recharge my creative energy. On the shelf, Modes of Criticism 4: Radical Pedagogy, edited by Francisco Laranjo (published by Onomatopee), immediately caught my eye. Though pocket-sized, the book is packed with rich ideas and collective reflections at the intersection of design education and social critique.

Design educator Danah Abdulla notes that education is inherently oriented toward radical change, as it shapes individuals and equips them with the capacity for critical thinking (P6). She emphasizes that “designerly ways of thinking and knowing provide students with tools for imaginative problem posing, enabling them to consider multiple paths toward possible solutions and to be self-reflexive practitioners and thinkers” (P5). Design itself, however, often can be informed by non-explicit actions and embedded within social infrastructures that may only become visible through practice—a view that resonates with Donald Schön’s observation in Designing: Rules, Types and Worlds (1988) that “designing is a social process.”

Activist and designer Maya Ober adds another dimension, emphasizing the importance of unlearning and questioning. We need to continuously shed biases inherited from family, relationships, environments, norms, and personal worldviews. This process is gradual, step by step, much like teaching itself. I especially appreciate Ober’s metaphor of teaching as a river, fluid, ever-moving, and not bound by rigid prescriptions, rules, or methodologies (P60). The process of teaching or learning is like a gradual, context-dependent movement.

Across these perspectives, one principle emerges clearly: whether in design, education, teaching, or learning, respect and inclusivity must remain foundational. As Dori Tunstall, former Dean of the Faculty of Design at OCAD University, reminds us in Decolonizing Design (2019), “Respectful design means acknowledging different values, different manners of production, and different ways of knowing.”

Last Friday, after a long day of uninspiring meetings, I ducked into the MIT Press bookstore in search of some intellectual nourishment to recharge my creative energy. On the shelf, Modes of Criticism 4: Radical Pedagogy, edited by Francisco Laranjo (published by Onomatopee), immediately caught my eye. Though pocket-sized, the book is packed with rich ideas and collective reflections at the intersection of design education and social critique.

Design educator Danah Abdulla notes that education is inherently oriented toward radical change, as it shapes individuals and equips them with the capacity for critical thinking (P6). She emphasizes that “designerly ways of thinking and knowing provide students with tools for imaginative problem posing, enabling them to consider multiple paths toward possible solutions and to be self-reflexive practitioners and thinkers” (P5). Design itself, however, often can be informed by non-explicit actions and embedded within social infrastructures that may only become visible through practice—a view that resonates with Donald Schön’s observation in Designing: Rules, Types and Worlds (1988) that “designing is a social process.”

Activist and designer Maya Ober adds another dimension, emphasizing the importance of unlearning and questioning. We need to continuously shed biases inherited from family, relationships, environments, norms, and personal worldviews. This process is gradual, step by step, much like teaching itself. I especially appreciate Ober’s metaphor of teaching as a river, fluid, ever-moving, and not bound by rigid prescriptions, rules, or methodologies (P60). The process of teaching or learning is like a gradual, context-dependent movement.

Across these perspectives, one principle emerges clearly: whether in design, education, teaching, or learning, respect and inclusivity must remain foundational. As Dori Tunstall, former Dean of the Faculty of Design at OCAD University, reminds us in Decolonizing Design (2019), “Respectful design means acknowledging different values, different manners of production, and different ways of knowing.”

The Clock of the Long Now: Time and Responsibility

August 30, 2025